Virginia Woolf & the Hogarth Press

Group show, Whittaker Gallery, Richmond

September 2016

Lily Briscoe’s Painting

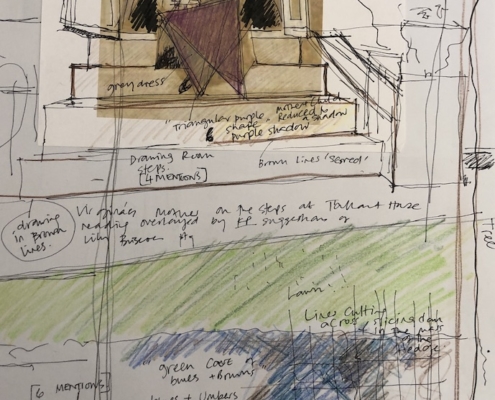

In To the Lighthouse, Virginia Woolf describes Lily Briscoe, an artist, standing in the garden making a painting. Throughout the novel, clues to the composition are given, amid descriptions of her struggles, dilemmas, lack of confidence, and fear of people looking at her work.

Kate Proudman often works in a collaborative way with a piece of written work as the starting point for a painting, and she was drawn to attempt Lily Briscoe’s painting from the description given throughout the novel. Reading the novel, Kate felt parallels with her own conflicts with composition, and echoes of her own desire to strike a balance between the figurative and the abstract.

The viewer is invited to look at the painting whilst listening to an audio recording of an extract read from the novel below:

“This ray passed level with Mr Bankes’s ray straight to Mrs Ramsay sitting reading there with James at her knee. But now while she still looked, Mr Bankes had done. He had put on his spectacles. He had stepped back. He had raised his hand. He had slightly narrowed his clear blue eyes, when Lily, rousing herself, saw what he was at, and winced like a dog who sees a hand raised to strike it. She would have snatched her picture off the easel, but she said to herself, One must. She braced herself to stand the awful trial of some one looking at her picture. One must, she said, one must. And if it must be seen, Mr Bankes was less alarming than another. But that any other eyes should see the residue of her thirty-three years, the deposit of each day’s living mixed with something more secret than she had ever spoken or shown in the course of all those days was an agony. At the same time it was immensely exciting. Nothing could be cooler and quieter. Taking out a pen-knife, Mr Bankes tapped the canvas with the bone handle. What did she wish to indicate by the triangular purple shape, “just there”? he asked. It was Mrs Ramsay reading to James, she said. She knew his objection— that no one could tell it for a human shape. But she had made no attempt at likeness, she said. For what reason had she introduced them then? he asked. Why indeed?—except that if there, in that corner, it was bright, here, in this, she felt the need of darkness. Simple, obvious, commonplace, as it was, Mr Bankes was interested. Mother and child then—objects of universal veneration, and in this case the mother was famous for her beauty—might be reduced, he pondered, to a purple shadow without irreverence. But the picture was not of them, she said. Or, not in his sense. There were other senses too in which one might reverence them. By a shadow here and a light there, for instance. Her tribute took that form if, as she vaguely supposed, a picture must be a tribute. A mother and child might be reduced to a shadow without irreverence. A light here required a shadow there. He considered. He was interested. He took it scientifically in complete good faith. …… But now—he turned, with his glasses raised to the scientific examination of her canvas. The question being one of the relations of masses, of lights and shadows, which, to be honest, he had never considered before, he would like to have it explained—what then did she wish to make of it? And he indicated the scene before them. She looked. She could not show him what she wished to make of it, could not see it even herself, without a brush in her hand. She took up once more her old painting position with the dim eyes and the absentminded manner, subduing all her impressions as a woman to something much more general; becoming once more under the power of that vision which she had seen clearly once and must now grope for among hedges and houses and mothers and children—her picture. It was a question, she remembered, how to connect this mass on the right hand with that on the left. She might do it by bringing the line of the branch across so; or break the vacancy in the foreground by an object (James perhaps) so. But the danger was that by doing that the unity of the whole might be broken. She stopped; she did not want to bore him; she took the canvas lightly off the easel….”

Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse